Swords of the Renaissance

The soldier of the mid-i

500s witnessed dramatic advances in military

technology. Swords, bows and pikes were now being

challenged by early artillery, hand-held guns and

complex siege weapons. In response, combatants

became more heavily armored. The sword evolved from

being a purely slashing weapon to one that could

pierce and break through plate armor. New sword

types also appeared, from the huge two-handed

broadsword of the Landsknecht to the handy

short-bladed falchion of the ordinary infantryman.

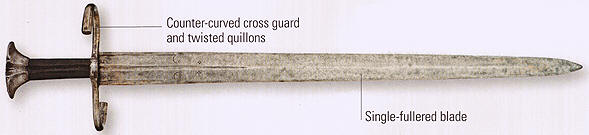

The Estoc or Tuck

Sword

Stiff, lozenge or

diamond-shaped thrusting blades were now replacing

the wide-bladed and cruciformhilted swords typical

of the medieval period. This new type of sword was

known to the French as an estoc and to the English

as a tuck. The estoc featured a long, two-handed

grip, enabling the bearer to achieve maximum effect

as he thrust the sword downwards into armor. This

sword was particularly effective at splitting

chainmail and piercing gaps in armor. Due to the

narrowness of the blade, it had no discernible

cutting edge but a very strong point. Opponents who

had lost the protection of their armor during the

heat of battle were still dispatched by the

traditional double-edged cutting sword, held in

reserve for just such an eventuality. Versatility

and a range of weapons to hand was still an

important and practical factor.

Downward-curving cross guard

ABOVE:

A Polish estoc, which would have been used by the

cavalry. The needle-like blade was ideal for

penetrating armor.

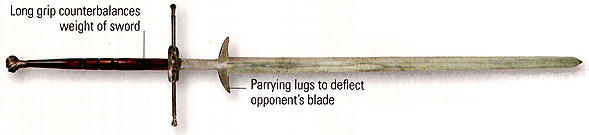

The

“hand-and-a-half” Sword

Common throughout

Europe from the beginning of the 15th century, the

“hand-and-a-half sword” is also referred to as a “longsword”.

The contemporary term “bastard sword” derives from

it being regarded as neither a one-handed nor a

two-handed sword. Despite these perceived drawbacks,

it possessed a reasonably long grip and shorter

blade, which allowed one hand to hold the narrow

grip firmly, while a couple of fingers placed

strategically on the forte gave the soldier extra

leverage and maneuverability when wielding. The

length of these swords was around 115—145cm

(45.3—57in).

ABOVE:

The “hand-and-a-half” sword has

a short

grip that

accommodates one hand, while the fingers of the

second hand are placed on the blade forte to allow

extra leverage and control when swinging the blade.

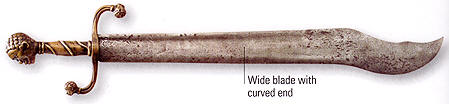

The Falchion

Although the

falchion’s design had originated in ancient Greece,

the sword experienced a widespread revival during

the Renaissance, particularly in Italy, France and

Germany. This short-bladed sword had a straight or

slightly curved blade, with cross guards either

absent or very simple.

The falchion was

primarily a side-weapon and was usually carried by

the infantry. Because of its short blade and ease of

maneuverability, the falchion became the precursor

to the hunting sword.

ABOVE:

This Milanese ceremonial falchion, c.1600,

features a strong, broad blade with curved,

double-edged point.

Two-handed (Zweihänder) Swords

Very large broadswords called Zweihänder or two-

handed swords, became very popular during the 15th

and 16th centuries, and are probably best known for

their association with the famed Landsknechte, or

mercenaries. Established during the reign of the

Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian 1(1459—1519), and

drawn mainly from Germany and eastern Europe,

Landsknechte fought in numerous battles throughout

the continent, particularly during the Italian Wars

of 1494—1 559.

ABOVE:

A two-handed Zweihänder sword from

c.1550,

used by mercenaries employed by the Holy Roman

Emperor.

Their Zweihänder swords had a length of up to 1 .8m

(5.9ft) and weighed 2—3.5kg (4.4—7.7lb). The hilt

was of massive form, with extremely large

pommels and hilt

guards. The sword could also be utilized as a form

of short lance when gripped firmly at the blade

forte. Because of its immense size, the Zweihänder

would also have been extremely effective at

attacking and breaking up massed ranks of infantry

or pikemen.

Another sword

favored by the Landsknechte was the Katzbalger

(cat-skinner or brawler), a short sword, or hanger.

It was a sturdy, wide-bladed sword, with a

distinctive “figure-of-eight” guard. It was 75—85cm

(29.5—33.5in) long. The sword’s name is thought to

derive from the practical reality that it would have

been a weapon of last resort and used in close,

confined combat, when the soldier would literally

have to fight like a cornered feral cat. The

Landsknecht carried it alongside his Zweihänder.

ABOVE:

The Katzbalger was a secondary sword of the

Landsknecht, and used when his larger, two-handed

sword was unavailable.

The Cinquedea, or

“five-fingered” Sword

Another distinctive short sword that developed in

Italy during the Renaissance was the cinquedea. The

shape and form of the cinquedea typifies the

Renaissance belief in the importance of artistry,

combined with a newly rediscovered passion for the

classical world. It was worn mainly with civilian

dress and comprised a very wide blade of

five-fingered span. The hilt was normally of

simple form, with a severely waisted grip. Because

of its wide blade, many swordsmiths took the

opportunity to embellish the swords with exquisite

engraving and gilding. The sword would have been

worn in the small of the back in order that it could

be drawn laterally.

There is some debate as to

whether the cinquedea was actually a dagger rather

than a sword. The average length is noted at

40—50cm/16—l9in (and there are even two-handed

versions known), so this probably indicates that the

cinquedea fits more comfortably within the broad

family of swords rather than dagger types.

ABOVE:

A cinqueda sword, with typical

pronounced medium ridge, or spine, running down the

centre of the blade.

Ceremonial Swords

The

increasing power and wealth of the European

monarchies and city states during the Renaissance

meant that the sword did not only serve a purely

military function. It also became a manifestation of

the rank and status of the privileged, and its most

notable appearances were at royal coronation

ceremonies. Although the medieval cruciform-hilted

sword had fallen out of favor on the Renaissance

battlefield, being superseded by more complex and

enclosed-hilt forms, it was still retained for

ceremonial purposes

—

perhaps recalling a

more “knightly” time

—

when a gentleman or

courtier swore allegiance to his king by the kiss of

a knightly sword. These “bearing” swords were

carried before kings, queens and senior clergy. The

sword of Frederick I of Saxony, presented to him by

Emperor Sigismund I of Germany in 1425, has a

cruciform hilt inset with rock crystal and heavily

gilded in gold and silver. There is also a massive

15th-century bearing sword, supposedly made for

either Henry V of England or Edward, Prince of

Wales, which has a total length of over 228cm

(88.6in). Ceremonial swords were also presented as

symbols of state office. From the 14th century

onwards, English mayors were granted the right

(usually by the monarch) to carry a great civic

sword on ceremonial occasions. This tradition was

upheld for centuries and many historic towns in the

United Kingdom still retain these swords. The

earliest recorded civic sword still in existence is

to be found in Bristol and is thought to date from

around 1373. Constables of France, including such

notables as Bertrand du Guesclin and Anne de

Montmorency, carried bearing swords. The

increasing power and wealth of the European

monarchies and city states during the Renaissance

meant that the sword did not only serve a purely

military function. It also became a manifestation of

the rank and status of the privileged, and its most

notable appearances were at royal coronation

ceremonies. Although the medieval cruciform-hilted

sword had fallen out of favor on the Renaissance

battlefield, being superseded by more complex and

enclosed-hilt forms, it was still retained for

ceremonial purposes

—

perhaps recalling a

more “knightly” time

—

when a gentleman or

courtier swore allegiance to his king by the kiss of

a knightly sword. These “bearing” swords were

carried before kings, queens and senior clergy. The

sword of Frederick I of Saxony, presented to him by

Emperor Sigismund I of Germany in 1425, has a

cruciform hilt inset with rock crystal and heavily

gilded in gold and silver. There is also a massive

15th-century bearing sword, supposedly made for

either Henry V of England or Edward, Prince of

Wales, which has a total length of over 228cm

(88.6in). Ceremonial swords were also presented as

symbols of state office. From the 14th century

onwards, English mayors were granted the right

(usually by the monarch) to carry a great civic

sword on ceremonial occasions. This tradition was

upheld for centuries and many historic towns in the

United Kingdom still retain these swords. The

earliest recorded civic sword still in existence is

to be found in Bristol and is thought to date from

around 1373. Constables of France, including such

notables as Bertrand du Guesclin and Anne de

Montmorency, carried bearing swords.

RIGHT:

Sword and scroll of Anne de Montmorency, 1493—1567,

from the

Hours of Constable Anne de Montmorency.

In terms of sheer brilliance of decoration and

craftsmanship, the ceremonial swords presented by

the Renaissance popes must rank as the apogee of

16th-century sword decoration. Given with a richly

embroidered belt and cap by the pope each year on

Christmas Day, invariably to members of the European

Catholic nobility, these great two-handed swords

were fabulously ornate and featured a profusion of

precious stones and extensive gold and silver

metalwork.

The

Development of Hunting Swords The

Development of Hunting Swords

Hunting had always been the favored and exclusive

pursuit of the nobility since the early medieval

period and Renaissance hunters continued this

pastime with vigor. The depiction of the royal hunt

was a popular subject for artists and many painters

and weavers of tapestry found the drama of the chase

and final kill with sword and spear irresistible.

The falchion sword, or short hanger, was well known

to the infantry as a side-weapon. It was first

adopted during the 14th century, specifically as a

dedicated hunting weapon. In later years, a saw-back

blade was also incorporated for ease of cutting up

the kill, followed by the development of a

specialist set of tools for pairing. This

combination of sword and skinning tools was known as

a garniture, or trousse. As the owners of these

hunting swords invariably had great financial means,

decoration of the swords became ever more elaborate.

RIGHT:

An

illustration of a hunting sword with pommel and

crossbar decorated by birds’ heads. It has a

saw-back blade for cutting the kill.

Swords of

Justice, Swords of Execution

Great swords were also employed as both symbols and

facilitators of judicial law. Many local courts of

justice placed a large bearing or executioner’s

sword on the courtroom wall. The presence of the

executioner’s sword was not purely symbolic for it

had a practical application in the actual beheading

of prisoners. It was often highly decorated and

engraved with prayers for the condemned, warnings

against transgressions and vivid images of

beheadings, hangings and torture.

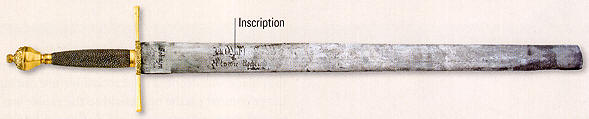

ABOVE

This German executioner’s sword has a double-edged

blade with a blunt, lightly rounded point. Many

surviving “execution swords” are actually swords of

justice which would be carried before the judge to

indicate his power over life and death.

ABOVE:

In this detail from the above sword, an etched

inscription

can be seen. In German it reads

“Ich Muf straffen daI verbrechen

—

Als wie Recht und Richter sprechen”.

Translated, this means “I have

to punish crime as the law and judge tell me”.

Executioners’ swords were more common in continental

Europe from the 1400s, particularly Germany, with

England still preferring the axe. The sword hilt was

normally of conventional cruciform shape with a

large counter-balancing pommel. It was very well

constructed, with high-quality steel used for the

manufacture of the blade. The blade edge was

extremely sharp and it was a requirement of the

executioner to keep it well honed so that the head

of the victim could be severed in one mighty blow.

Blades were broad and flat backed, with a rounded

tip. The sword was designed for cutting rather than

thrusting, so a pointed tip (as in the case of

military blades) was unnecessary.

An executioner’s

sword in the British Museum, London, has the

following words engraved on the blade in Latin. It

translates as: “When I raise this sword I wish the

sinner eternal life / The Sires punish mischief: I

execute their judgement.” When no longer used for

executions, swords became ceremonial.

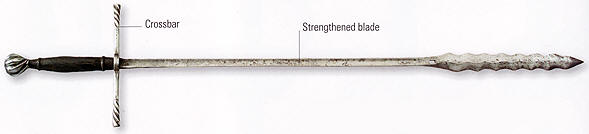

Another sword designed solely

for the hunt was the boar sword. Based on the

triangular-bladed estoc or tuck, its greatly

stiffened blade was designed to withstand the power

of a charging boar or other large animal. The boar

sword was introduced during the

14th century and by around 1500

it had developed a faceted or leaf-shaped spear

point. A crossbar was later added near the end of

the blade to prevent an animal running up the length

of the blade and so making it difficult to retrieve.

ABOVE:

A German boar sword, c.1530. Only the bravest

of hunters

used swords rather than spears for boar hunting.

The Rapier

Spain is normally cited as the

first country to have introduced the rapier, or

espada ropera (sword of the robe), during the

late 1400s. This designation highlighted the

new-found ability for a gentleman to wear these

swords with ordinary civilian dress, rather than

needing to don his armor. Italy, Germany and England

adopted the rapier soon afterwards.

ABOVE:

A German rapier dating from c.1560—70. It has

a large spherical pommel that counterbalances the

weight of the blade.

In its most complete and

recognizable form, the rapier came into full

prominence during the early 16th century. In the

mid- 1400s, precursors of the rapier (including the

standard cruciform-hilted sword) had begun to

develop a primitive knuckle guard and forefinger

ring or loop. By 1500, a series of simple bars were

joined to the knuckle guard to form a protective

hilt. At this time, the blade was still a wide,

cutting type, and it is only well into the 16th

century that the slender rapier blade was fully

developed. This typically thin blade was deemed

impractical for use during heavy combat on the

battlefield so the rapier was viewed primarily as a

“civilian” duelling sword. The new rapier hilt,

however, was adopted by the military but with the

retention of a wider, more traditional broadsword

fighting blade.

The Blade

Sword blades were manufactured

in Toledo and Valencia (Spain), Solingen and Passau

(Germany), and Milan and Brescia (Italy). They were

sold as unhilted blades and then hilted locally at

their eventual destinations throughout Europe. Some

blades are marked by their maker, although many are

plain. Notable bladesmiths’ names include Piccinino,

Caino, Sacchi and Ferrara from Italy, .Johannes,

Wundes and Tesche (Germany) and Hernandez (Spain)..

Respected names were often stamped on blades by

lesser-known rivals to enhance the value of an

inferior sword.

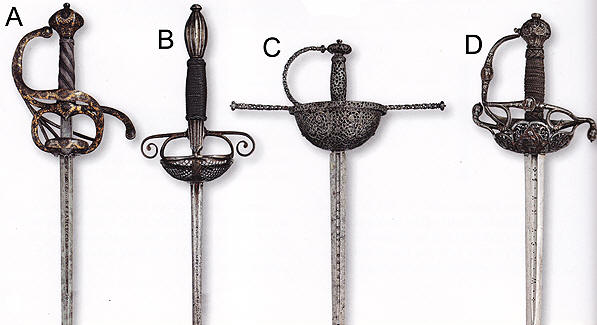

A) ABOVE:

Italian rapier, c.1610. Of true swept-hilt

form, it has deep chiseling to the knuckle guard.

B) ABOVE:

A North European dueling rapier, c.1635, with

a distinctive elongated and fluted pommel.

C) ABOVE:

A Spanish cup-hilt rapier, c.1660. The cup

and hilt are extensively pierced. It has very long,

straight, slender quillons with finials to each end.

D) ABOVE:

An English rapier with a finely chiseled cup hilt,

c.1650. The blade is stamped

“Sahagum”.

|