Medieval Weapons

Feudal armies in Europe from

the 11th to the 14th century produced a core group

of premium fighting men

— the mounted knights.

Over time, they became more heavily armored and

reliant upon the shattering force of horse, lance

and wide-bladed sword. In their wake, massed ranks

of foot-soldiers engaged the enemy with long

polearms (essentially weapons mounted on the end of

a long pole), hoping to dismount and finish off any

enemy knight. The fighting was brutal and bloody,

conducted in a crush of jabbing, thrusting weapons.

1066 - The

Battlefield

The

Battle of Hastings (1066) saw William of Normandy

(c.1028—1087)

unleash the devastating power of his heavily

armoured knights for the first time on British soil.

During many hours of hard fighting, King Harold II

(c.

1022—1066) and his

fellow Anglo-Saxon defenders were constantly harried

by repeated Norman cavalry charges. This type of

mounted and mobile warfare was unknown to the

Anglo-Saxons, who were predominantly foot soldiers,

and it was only their fortunate selection of

superior and defensible terrain prior to the battle

that stopped them from being immediately

overwhelmed. The

Battle of Hastings (1066) saw William of Normandy

(c.1028—1087)

unleash the devastating power of his heavily

armoured knights for the first time on British soil.

During many hours of hard fighting, King Harold II

(c.

1022—1066) and his

fellow Anglo-Saxon defenders were constantly harried

by repeated Norman cavalry charges. This type of

mounted and mobile warfare was unknown to the

Anglo-Saxons, who were predominantly foot soldiers,

and it was only their fortunate selection of

superior and defensible terrain prior to the battle

that stopped them from being immediately

overwhelmed.

RIGHT:

In

this detail from the Bayeux Tapestry, Harold Ii’s

Anglo-Saxon troops, led by an armoured standard

bearer and a warrior with an axe, confront a Norman

cavalryman armed with a lance.

The Norman War

Sword

A double-edged, razor-sharp

broadsword with an average length of around 75cm

(29.5in), was the main battle weapon of the Norman

knight of the medieval period. It was ideal for

swinging at speed and downward slashing. It would be

used one-handed and in conjunction with a large,

kite-shaped shield.

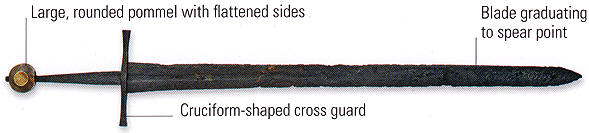

ABOVE:

This sword is a “transitional” piece

between the Viking and medieval period. It has a

distinctive “brazil nut” pommel that was common in

the early medieval period and the cross guard has

increased considerably in width, while the blade is

also more finely tapered.

The Norman

Lance

Although it is called a

lance, Norman knights used what could more

accurately be described as a long, wooden spear with

a simple, spiked end. It would be held firmly under

the arm in order that the maximum force of both man

and horse could be transmitted into the charge. Once

the enemy had been engaged, the lance could also be

transformed into an effective close-combat thrusting

weapon, or simply thrown.

The

“Knightly” or “Arming” Sword The

“Knightly” or “Arming” Sword

During a period when there

was a practical need for a substantial and sturdy

fighting weapon on the battlefield, the medieval

“knightly” or “arming” sword was carried. Most

battles in Europe took the form of two heavily armed

and armored scrums locked in a frenetic

life-or-death struggle to push the enemy back,

coupled with the added difficulty of trying to kill

or maim as many enemies as possible in a very

limited amount of space. It was quite common for

soldiers to be literally crushed to death by their

own side as the battle moved along.

Sword Manufacture

Before the 9th century good sources of quality iron

ore were not always available and many swords were

often forge-welded from a selection of smaller iron

pieces, thus reducing the inherent strength of the

blade. Conversely, swordsmiths also forged

high-quality swords using a process known as pattern

welding, using rods of superior iron. The process

required that the rods be tightly twisted together,

so creating a much stronger and more durable blade

with great qualities of tempering. The interlocking

of these rods under great heat, and their sudden

cooling and hammering, created distinctive forging

patterns on the blade’s surface. This diversity of

swirling patterns was highly prized by an owner.

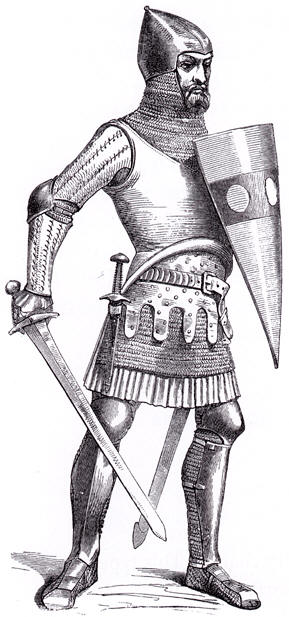

RIGHT:

A 13th-century French soldier. He carries a double-

edged broadsword with brazil nut pommel and

down-sloping cross guard.

By the 9th century in Europe, the blast furnace

became widespread and the need for pattern welding

diminished. During the centuries that followed, the

technique was slowly lost, and by 1300 there are few

examples of its use. The technique survived,

however, in Scandinavia, where good quality iron

ores and charcoal were widely available.

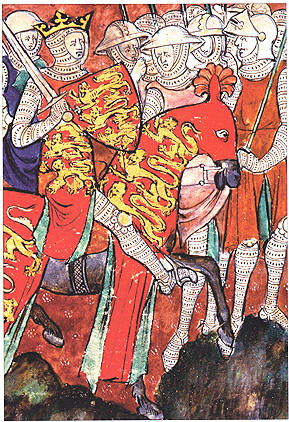

ABOVE:

William the Conqueror, accompanied by knights and

soldiers, from a page of illustrated Latin text from

the 14th century.

The

typical style of the “knightly” or “arming” sword

was firmly established by the 12th and 13th

centuries. In general terms, it comprised a long,

broad-bladed cutting and thrusting sword with double

fullers (beveled grooves); a plain crossbar hilt;

and a wheel, brazil nut, ovoid or mushroom- shaped

pommel. This sword design had remained virtually

unchanged since the Viking invasions (AD793—c.

1066), and over the next three centuries there was

to be little innovation. Most blades and hilts were

plain, although some surviving blades are found with

inlaid decoration, mostly in the form of large,

punched lettering or symbols, normally of a

religious or mystical nature. Pommels of this period

can also be found with inset heraldic devices,

denoting particular royal or noble families. Rare

specimens have pommels of agate, inlaid gold or rock

crystal. The

typical style of the “knightly” or “arming” sword

was firmly established by the 12th and 13th

centuries. In general terms, it comprised a long,

broad-bladed cutting and thrusting sword with double

fullers (beveled grooves); a plain crossbar hilt;

and a wheel, brazil nut, ovoid or mushroom- shaped

pommel. This sword design had remained virtually

unchanged since the Viking invasions (AD793—c.

1066), and over the next three centuries there was

to be little innovation. Most blades and hilts were

plain, although some surviving blades are found with

inlaid decoration, mostly in the form of large,

punched lettering or symbols, normally of a

religious or mystical nature. Pommels of this period

can also be found with inset heraldic devices,

denoting particular royal or noble families. Rare

specimens have pommels of agate, inlaid gold or rock

crystal.

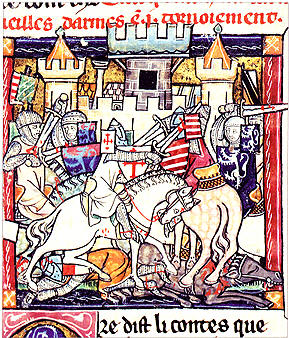

RIGHT:

The knights Galahad and Gawain are pictured taking

part in a tournament, from La Queste el Saint

Graal, c.1316. The knights wield wide-bladed,

slashing swords typical of this period.

Swords would have been pattern

forged or “braided” in the manner of earlier Viking

swords, making them excellent fighting weapons

— very strong and not

prone to breakage. Swords were normally combined

with either a large shield or buckler (small

shield), although there are many contemporary images

and written descriptions that describe the use of

the knightly sword without a shield. This was

thought to enable the free hand to grab or grapple

with opponents. A knight would have worn this large

sword whether in armor or not. He would have been

considered “undressed” without his sword.

Medieval

Ceremonial Swords

Swords

produced specifically for use at royal coronations

and similar ceremonies began to appear from the 11th

century onwards. They were not designed for battle

and were kept safely in churches, palaces and state

arsenals. Decoration was profuse and the scale was

deliberately large and impressive. One of the swords

of Charlemagne (or Charles the Great), King of the

Franks (r AD742—814), is preserved in the

Schatzkammer (Treasury) in Vienna. The blade is

single-edged, slightly curved and overlaid with

copper decoration, including dragon motifs. Hilt and

scabbard are covered in silver gilt. The grip is

wrapped in fishskin, set at an angle and very

reminiscent of Near Eastern swords of the period.

The second sword sometimes attributed to Charlemagne

is found in the Louvre, Paris. The ornamentation on

the hilt suggests it was carried by him, but it was

also known to have been used as a ceremonial sword

when Philip the Bold was crowned in 1270. Swords

produced specifically for use at royal coronations

and similar ceremonies began to appear from the 11th

century onwards. They were not designed for battle

and were kept safely in churches, palaces and state

arsenals. Decoration was profuse and the scale was

deliberately large and impressive. One of the swords

of Charlemagne (or Charles the Great), King of the

Franks (r AD742—814), is preserved in the

Schatzkammer (Treasury) in Vienna. The blade is

single-edged, slightly curved and overlaid with

copper decoration, including dragon motifs. Hilt and

scabbard are covered in silver gilt. The grip is

wrapped in fishskin, set at an angle and very

reminiscent of Near Eastern swords of the period.

The second sword sometimes attributed to Charlemagne

is found in the Louvre, Paris. The ornamentation on

the hilt suggests it was carried by him, but it was

also known to have been used as a ceremonial sword

when Philip the Bold was crowned in 1270.

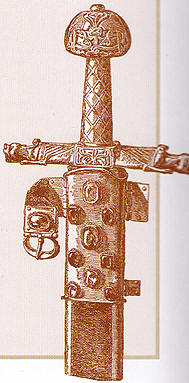

RIGHT:

A

line drawing of one of two swords attributed to

Charlemagne or Charles the Great

(r

AD742—814). The sword is kept in the Louvre Museum

in Paris.

ABOVE:

A

knight’s sword, c.1250—1300, with a narrow blade,

light enough to use on foot. This sword has a

spear-point blade and impressive cutting and

thrusting capabilities.

ABOVE:

A longsword with a highly tapered blade which could

be used to penetrate armor.

The Medieval Sword in Battle

A contemporary Florentine

description of the Battle of Kosovo, between the

Serbs and the Ottoman Empire in 1389, highlights the

“knightly” aspect of the use of the sword and its

perceived retributory power.

Fortunate, most

fortunate are those hands of the twelve loyal

lords who, having opened their way with the

sword and having penetrated the enemy lines and

the circle of chained camels, heroically reached

the tent of Amurat himself

. .

Fortunate above

all is that one who so forcefully killed such a

strong vojvoda by stabbing him with a sword in

the throat and belly. And blessed are all those

who gave their lives and blood through the

glorious manner of martyrdom...

Response from the Florentine Senate

(1389)

The Medieval

Longsword

A

natural progression from the two-handed “arming” or

“knightly” swords of the early to mid-medieval

period was the first longswords, with the main

difference being an increase in blade length. The

double-edged blade was 80—95cm (31—37 in) long and

weighed in at approximately 1—2kg (2.2—4.4 lb). This

was very much a sword of the late medieval period

and was used from around 1350 to 1550. The length of

the grip was also extended to allow a more powerful

and directed use of two hands, but the traditional

cruciform hilt was still retained. A

natural progression from the two-handed “arming” or

“knightly” swords of the early to mid-medieval

period was the first longswords, with the main

difference being an increase in blade length. The

double-edged blade was 80—95cm (31—37 in) long and

weighed in at approximately 1—2kg (2.2—4.4 lb). This

was very much a sword of the late medieval period

and was used from around 1350 to 1550. The length of

the grip was also extended to allow a more powerful

and directed use of two hands, but the traditional

cruciform hilt was still retained.

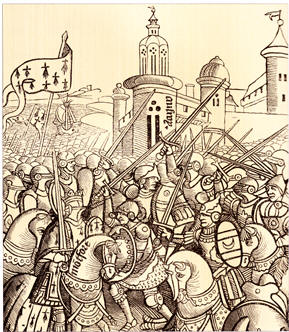

RIGHT:

A 14th-century French battle scene.

The chaotic nature of a medieval battle is very

evident.

The longsword was a new

departure in sword design and this innovation was

soon witnessed in its battlefield application. It

had the usual cutting

functions expected of a broadsword but the blade

profile had become thinner and was now designed

(through stiffening of the blade tip) to thrust and

penetrate plate armor. The longsword would come to

prominence during the Renaissance, when the

battlefield became a testing ground for new forms of

penetrative edged weapons. The terms

“hand-and-a-half sword, greatsword and bastard sword

are different classifications of swords of this

period.

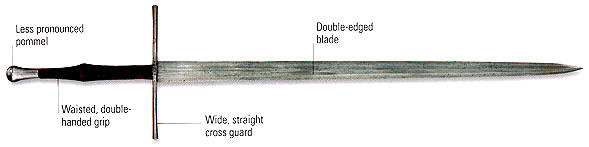

ABOVE

A two-handed longsword of the later medieval period,

with waisted grip (tapering towards the pommel) for

comfortable handling.

|