Ancient Roman Weapons

The army of ancient Rome

(800Bc—AD476) was a formidable fighting force

—

well disciplined, organized and

supplied with an array of effective and

battle-proven weapons. The sword and spear were the

infantryman’s main weapons, and the spectacular

military successes of the Roman legions throughout

Europe and the Near East lay in the disciplined

battlefield application and relentless training in

the use of these weapons.

The

Gladius The

Gladius

A short stabbing

weapon with a blade length of around 50—60cm

(19.6—23.6in), the gladius was the primary fighting

sword of the Roman soldier. Its origins are somewhat

uncertain, simply because very few examples have

been unearthed by archaeologists and the only

identifiable gladii have come not from Italy but

from Germany. This sword was described by the

ancient Romans as the “gladius hispaniensis”, in

recognition of a similar type of Celtic design

encountered by the Romans during their conquest of

Hispania (modern-day Spain) during the Second Punic

War (218—201BC). Before this, Roman soldiers would

have used swords of Greek origin.

The hilt, or capulus,

of the gladius featured a rounded grip, moulded with

four finger ridges to allow a comfortable and firm

hold upon the sword. Pommels were bulbous and

normally of plain form. The scabbard was made of

wood, covered with leather and strengthened by a

rigid frame of brass or iron.

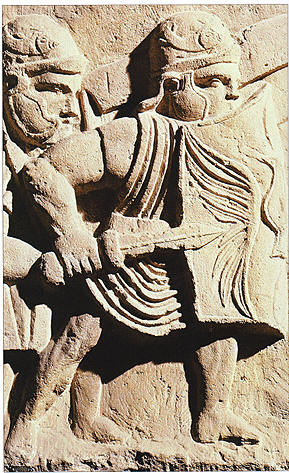

RIGHT:

Legionaries, carrying gladius swords, are depicted

during battle in a relief carving from the base of a

column found at Magonza, Italy.

Wearing the

Gladius

Although in later

centuries most swords would be worn traditionally on

the left side, the gladius was worn on the right

side. This allowed the wearer to draw with the right

hand and at the same time carry a heavy shield in

the left hand. This can be confirmed from the

depictions of Roman soldiers on tombstones, wall

paintings and friezes. The tombstone of Annaius

Daverzius, an auxiliary infantryman who served with

the Cohors III Delmatarum, a Roman garrison

stationed in Britain during the 1st century AD,

shows his sword attached on the right side of his

belt by four suspension rings. As an acknowledgement

of his status, a centurion was allowed to wear his

sword on the left.

The Gladius in

Battle

If used with enough force and

directed at the most vulnerable parts of the body,

particularly the stomach, the stab of a gladius

blade into the flesh of an opponent was nearly

always fatal.

Roman soldiers fought as a

single fighting unit within an organized and massed

formation. This fighting block comprised hundreds of

men standing shoulder

to shoulder. They had to keep this formation solid

and it was crucial, therefore, that all soldiers

fought with the gladius placed in their right hand.

Any left-handed recruit would have this hand

strapped behind his back during training, and it

would be kept tied until he learned to fight with

the right hand as well as he would have done with

the left. Wearing the gladius on the right also

meant that the drawing of the sword would not

interfere with soldiers on either side, and would

also not restrict the use of the Roman scutum (the

shield).

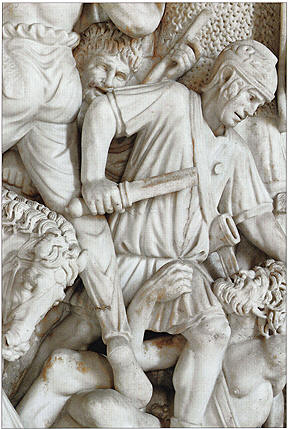

ABOVE:

A battle between Roman and Germanic

armies, depicted as a relief on a marble

sarcophagus,

C.

AD18O—190.

The Roman line would wait for the enemy to come

right up to it and then await the order to advance.

Upon receiving this order, all soldiers would take

one step forward and thrust their shields, or scuta,

into the bodies and faces of the enemy, causing them

to lose their balance and so render them temporarily

vulnerable. The shield was then quickly withdrawn

and the gladius thrust into the body of the

opponent. The Roman soldier was taught to deploy the

gladius horizontally, so piercing the enemy’s ribs

and penetrating to his vital organs.

ABOVE:

A

gladius and scabbard, which belonged to an officer

of Tiberius

(42Bc—AD37),

the

second Emperor of Rome.

ABOVE:

A

stone depiction of the Emperor Hostilianus in a

Roman battle scene, 251AD. He is carrying a gladius,

of which the blade is broken.

The Spatha

By the middle of the 1st century AD, the gladius had

been replaced by the spatha (spada

is the modern-day

Italian word for sword). It had a much longer blade

(60—80

cm123.6—3

1 .5in) and shorter

point. The sword was Celtic in origin and it is

probable that Gallic cavalry (from Gaul, in

modern-day France), in the employ of Rome,

introduced the sword to the Roman Army during the

time of Julius Caesar (100—44Bc) and Augustus

(63Bc—14). It was a slashing weapon and designed to

be used by both the Roman cavalry and infantry.

ABOVE:

Found in Spain, this is the only known actual

example of a spatha with an eagle-headed hilt. It

would have been used by a tribune in the early 4th

century

AD.

The Manufacture

of Swords

By the time of the Roman Republic (c.509—44BC),

the use of steel in the manufacture of swords was

well advanced and Roman swordsmiths smelted iron ore

and carbon in a bloomery furnace (the predecessor of

the blast furnace). The temperatures in these

furnaces could not achieve the high levels required

to fully melt the iron ore, so the swordsmith had to

work with pieces of slag (residue left after

smelting) or bloom (mass consisting mostly of iron),

which were then forged into the required blade

shape. These pieces or strips of cooling metal were

welded together for increased blade strength. During

this process the owner’s initials or full name were

sometimes engraved onto the blade.

The Pilum

Around 2m (6.5ft) in length, the main heavy spear or

javelin used by the Roman Army was the pilum. It

consisted of a socketed iron shank with a triangular

head. The pilum weighed in at around 3—4kg

(6.6—8.8lb); later versions produced during the

Empire (27BC—AD476) were lighter. The pilum would

have been thrown by charging legionaries and could

easily penetrate shield and armour from a range of

around 1 5m (49.2ft). A lighter, thrusting spear,

the hasta, was also used for close-combat

situations.

The narrow, spiked shape of the spearhead meant that

when it became stuck in the wood of an opponent’s

shield it was extremely difficult to dislodge, so

disrupting the opponent at a critical moment of

battle. He might have to relinquish his shield,

leaving himself extremely vulnerable to the oncoming

Roman infantry. Even if he was able to remove the

spear, he couldn’t throw it back at the Romans

because the soft iron of the spear shank meant that

it bent on impact and so became useless as a weapon.

In the aftermath of a Roman victory, used pila were

gathered from the battlefield and sent back to the

Roman Army blacksmiths for straightening. The Roman

military strategist Vegetius (c.

AD450) comments on

the effectiveness of the pilum:

As to the missile

weapons of the infantry, they were javelins

headed with a triangular sharp iron, eleven

inches or afoot long, and were called piles.

When once fixed in the shield it was impossible

to draw them out, and when thrown with force and

skill, they penetrated the cuirass without

difficulty... from De Re Militari (c.AD430)

Later, a further development of

the pilum was introduced: the spiculum. Vegetius

notes its power:

They had likewise

two other javelins, the largest of which was

composed of a stafffive feet and a half long and

a triangular head of iron nine inches long. This

was formerly called the pilum, but now it is

known by the name of spiculum. The soldiers were

particularly exercised in the use of this

weapon, because when thrown with force and skill

it often penetrated the shields of the foot and

the cuirasses of the horse... from

De Re Militari

(c.AD430)

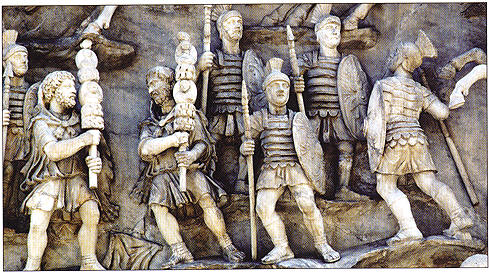

ABOVE:

Roman soldiers carrying light spears (lancea) and

shields. Detail of a relief from the Antonine

Column, Rome, erected

c.AD180—196

in recognition of the Roman victory in battle over a

Germanic tribe.

ABOVE:

Dating from

AD70,

this inscribed Roman commemorative stone depicts a

horseman (Vonatorix) wielding a spear.

The Contos

A long, wooden

cavalry lance which was 4—5m (13.l—16.4ft) in

length, the contos derived its name from the Greek

word kontos, or “oar”, which probably gives

some indication as to the length of the lance. It

took two hands to wield, so the horseman had to grip

his mount by the knees. To be able to do this

effectively would have taken considerable strength

and training.

ABOVE:

Made in the Roman provincial style, this contos

lance head dates from the 2nd century

AD.

|