Ancient

Egyptian Weapons

The

Egyptian armies of the Old Kingdom (c.2649—2134BC)

and Middle Kingdom (c.2040—1640BC) fought primarily

on foot and in massed ranks. Their soldiers were

lightly equipped with shield, bow, spear and axe.

The constant wars and invasions of the later

dynasties brought with them the assimilation and

transference of diverse military technologies. This

greatly expanded their range of weapons, which

diversified to include plate armor, chariots and,

more importantly, the sword.

Introduction of the Sword

Following the collapse of central government in

Egypt due to internal rebellion, the Hyksos peoples

of Palestine took advantage of this instability and

invaded Egypt around 1640BC. They ruled Egypt for

over 200 years and brought with them striking

advances in weapon making, particularly the use of

metal in the manufacture of swords and edged

weapons.

The adoption of the sword in ancient Egypt was a

direct consequence of the introduction of metal.

Prior to this, axes and spears were fashioned from

flint, and swords were simply not available. Copper

had already been utilized for some time, but bronze

was the first material consistently used for sword

blades, as it was much harder and easier to work.

Sickle-shaped swords (originally inherited from the

Sumerians) were gradually replaced by swords with

slightly curving blades. The “Sea Peoples”, invaders

from the Aegean and Asia Minor who first attacked

Egypt during the reign of Merenptah (1213—1202BC),

also introduced straight, two-edged blades with

sharp, stabbing points. Contemporary depictions of

battles show massed infantry using both jabbing and

slashing

swords.

The

Influence of Iron The

Influence of Iron

Throughout the Mediterranean during the New Kingdom

period of Rameses III (c.1186—1155BC), the smelting

of iron ore had a direct impact on Egypt, enabling

swords to be produced with much longer and sturdier

blades. Examples of swords with blade lengths of up

to 75cm (30in) have been unearthed from royal tombs.

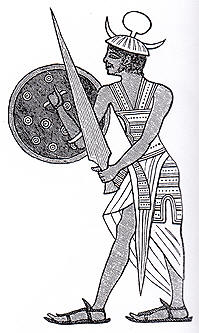

This ancient Egyptian warrior is depicted carrying a

long, double-edged and broadbladed sword. It is

probably a one-piece construction.

The Spear

Primarily a weapon used for hunting, the Egyptian

spear never surpassed the bow and arrow, which

remained the standard weapon of the Egyptian Army.

During the Old Kingdom (c.2649—2134BC) and Middle

Kingdom (c.2040—1640BC), simple pointed

spearheads were constructed from either flint or

copper and attached to long wooden shafts by means

of a tang (the hidden portion or “tongue” of a blade

running through the handle). In the later New

Kingdom (c.1550—l070BC), stronger bronze

blades were secured by a more reliable socket.

Spears were made for

either throwing or thrusting, and were especially

useful when chasing fleeing enemies and stabbing

opponents in the back. They were regarded primarily

as auxiliary weapons and called upon by charioteers

when they had spent all their arrows and needed some

form of close protection. The following description

of Amenhotep II’s victory at the Battle of

Shemesh-Edom c.1448BC (in Upper Galilee, now

modern-day

Israel) is recorded at the Temple of Karnak (built

over a period of some 1,600 years from around

l500BC), near Luxor in Egypt: Spears were made for

either throwing or thrusting, and were especially

useful when chasing fleeing enemies and stabbing

opponents in the back. They were regarded primarily

as auxiliary weapons and called upon by charioteers

when they had spent all their arrows and needed some

form of close protection. The following description

of Amenhotep II’s victory at the Battle of

Shemesh-Edom c.1448BC (in Upper Galilee, now

modern-day

Israel) is recorded at the Temple of Karnak (built

over a period of some 1,600 years from around

l500BC), near Luxor in Egypt:

Behold His Majesty was

armed with his weapons and His Majesty fought

like Set in his hour. They gave way when His

Majesty looked at one of them, and they fled.

His Majesty took all their goods himself with

his spear... Karnak Stele of Amenhotep II,

from W.M. Flanders Petrie, A History of

Egypt, Part Two.

ABOVE:

Carved by an unknown Egyptian artist during the 18th

Dynasty, c.1567—1320BC, this relief depicts two

soldiers, one carrying a spear.

The Khepesh -

Sword of the Pharaoh

ABOVE:

An Egyptian bronze khepesh sword with a handle

inlaid with ivory. The sword comes from El Ivory

handle Rabata and dates to the New Kingdom, c.1250BC.

Originally a throwing weapon of sickle-sword shape,

the khepesh could also be used as a conventional

slashing or cutting sword. It appears to have been a

favored weapon of the Pharaoh, as he is often

depicted wielding it against enemies or during a

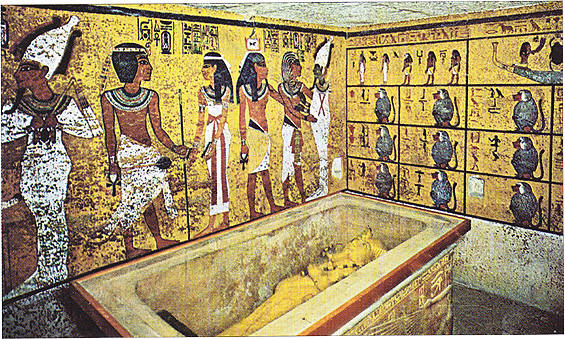

hunt. The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun

(r.c.1361—1352Bc) by Howard Carter in 1922 revealed

remarkable insights into the lives of ancient

Egyptians. One of the numerous objects found in the

tomb included a ceremonial shield, which depicted

the young Pharaoh “smiting a lion” with a khepesh.

ABOVE:

The Tomb of Tutankhamun. The king is depicted in a

number of battle scenes, although it is not known

whether he actually took part in any campaigns.

The Battle-axe

There were two distinct types

of battle-axe used by the Egyptian soldier: the

cutting axe and the piercing axe. The cutting axe,

used during the early kingdoms, had a head attached

to a long handle and would have been used at arm’s

length. The blade head was attached to the handle

through a groove and then tightly bound with leather

or sinew. This axe was especially effective against

opponents who wore little body armor, particularly

Egypt’s African enemies, like the Nubians. It was

usually deployed after the enemy had been routed

(often by the archers), rather than as a weapon

against massed ranks.

The cutting axe was later

superseded by the piercing axe that was designed to

penetrate armor. Unlike contemporary Asiatic

societies (especially the Sumerians and the

Assyrians), who used a blade cast with a hole

through which the handle was inserted and firmly

attached by rivets, the Egyptians continued to use

the antiquated method of a mortise-and-tenon joint

(a tenon is a tongue that slots into a hole called

the mortise) to fix the blade to the handle. This

made the battle-axe inherently weaker. During the

invasion by the Hyksos around 1640Bc, this obsolete

weaponry, coupled with the invaders’ use of

horse-drawn chariots, long swords and stronger bows,

proved fatal for the lightly armed Egyptians.

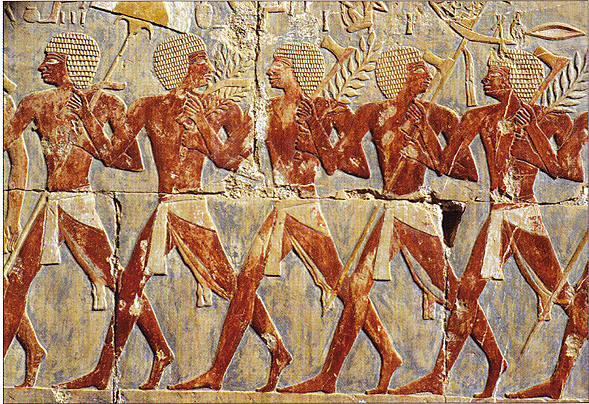

ABOVE

A painted relief of light infantry with standards,

battle-axes and palm fronds, from the temple of

Hatshepsut in Thebes, Egypt, c.1480BC.

|